An Introduction to Educational Video Games

Contents |

Why teach with games?

Educational theory

- Video games are a medium that incorporates both new and traditional literacies. Games can consist of written text, music, spoken words, animation, still images and interaction. Playing a game can help build skills in understanding the meaning behind each of these component parts—that is, playing a game can help build the player's literacy skills.

- Games often incorporate good teaching techniques, because they have to teach players how to play them. Here are some examples of how common elements of video games resemble established pedagogical techniques:

- Tutorials, which teach players about a game's rules, interface and controls, are often presented in a way reminiscent of Gagne's Nine Events of Instruction.

- Many games encourage certain in-game actions by rewarding players with better equipment or other benefits. These rewards are usually provided in ways that correspond to the Behaviorist technique of variable ratio reinforcement.

- Online games, including games built around social multiplayer elements, recall Vygotsky's ideas about how culture and social interaction are central to learning (social constructivism).

- Games often introduce rules one at a time, allowing players to become familiar with simpler gameplay before ratcheting up the complexity. This echoes another of Vygotsky's ideas: the zone of proximal development.

- Video games do a good job of presenting information in ways that "digital natives" (students who grew up with computers and the internet) tend to prefer. For example, games can present simulations of concepts at work, which players can then experiment with. Games can also incorporate systems for on-demand access to information, rather than needing to present it sequentially.

- Video games can be a powerful persuasive tool. Because they can incorporate elements including written and spoken text, music and video, many traditional modes of communication can be embedded in video games. However, games can also convey information through social interaction, as well as through the very rules that make up the game.

Practical examples

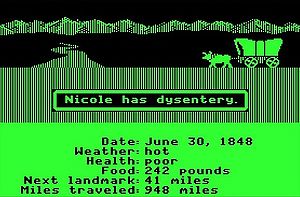

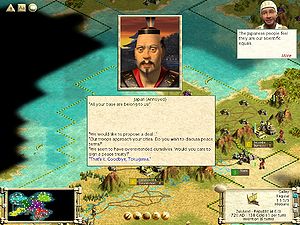

Civilization III

"Within just a few weeks, all of the participants showed dramatic improvements in their basic geography and history skills. Most could locate the major ancient civilizations on a map, and all could name key historical military units, as well as make arguments about the growth of cities in particular geographic areas. Students were skilled with collegiate-level world history terminology, using words and terms such as monotheism, cathedral and ancient Persians regularly."

Squire also notes that the learning did not stop when the students stopped playing. All of the participants "checked out books, completed school reports, and regularly engaged in voluntary learning activities stemming from their gameplay."[1]

Neverwinter Nights

Fantasy role-playing game Neverwinter Nights has been used to help students improve reading skills, and as a technological platform for students to create interactive short stories. High school teacher Megan Glover Adams found that the game's unusual fantasy vocabulary provided an appropriate challenge for strong and weak readers alike, encouraging "model reading behaviors."[2]Neverwinter Nights also comes with a powerful set of creative tools that allows users to craft their own fantasy stories that can be played within the game. One Canadian research group reported that high school students were able to create "sophisticated interactive stories with very little training" using these tools.[3]

A similar English study found that middle and high school-age students were so highly motivated to create stories using the same Neverwinter Nights tools that they had to be "actively discouraged from cutting short their lunchtimes."[4]

Game-based novels

Games can be useful to educators even when they are not played in school, or specifically for any school activity. Middle school teacher Kristie Jolley found that her students' engagement in the fictional worlds of games like World of Warcraft (a fantasy role-playing game with a detailed setting) and Halo (a science-fiction shooter about an interstellar war) helped her direct them to reading activities that they otherwise avoided. Many popular video game franchises have tie-in novels in addition to Halo and World of Warcraft.[5]Learning more

These are just a few examples of ways that you can use games to teach, and of reasons why it makes sense to do so. There's much more information out there, including right here on The Educational Games Database. If you'd like to know more about how games work, check out some of the terms in our glossary of game genres and mechanics. If you're ready to move on to the intermediate-level articles, start by reading about how to teach using content-aligned video games. An in-depth article about how to teach games as texts is also available.

References

- ↑ Squire, Kurt D. Video Games and Education: Designing Learning Systems for an Interactive Age. Educational Technology Magazine: The Magazine for Managers of Change in Education (2008) vol 28 (2) pp. 17-26. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/detail?accno=EJ792151.

- ↑ Adams, Megan G. Engaging 21st-Century Adolescents: Video Games in the Reading Classroom. English Journal (2009) vol 98 (6) pp. 56-9. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/detail?accno=EJ846025.

- ↑ Carbonaro, M., et al. Interactive Story Authoring: A Viable Form of Creative Expression for the Classroom. Computers & Education (2008) vol. 51 (2) pp. 687-707. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/detail?accno=EJ795993.

- ↑ Robertson, Judy, and Judith Good. Children's Narrative Development through Computer Game Authoring. TechTrends: Linking Research & Practice to Improve Learning (2005) vol. (5) pp. 43-59. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/detail?accno=EJ737696.

- ↑ Jolley, Kristie. Video Games to Reading: Reaching Out to Reluctant Readers. English Journal (2008) vol. 97 (4) pp. 81-6. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/detail?accno=EJ788591.